by Eric Hosick (erichosick@interfacevision.com)

Let’s use biological classification as our taxonomy.

The way mental models are formed between the three domains of literature, music and art are very different. Similar then is textual programming languages and visual programing languages: both different domains.

For each domain, there are different ways to form mental models. For example, within the kingdom of textual languages we have functional, declarative, and object oriented. These also greatly differ in how we understand and form mental models of the programs being created.

This blog is within the context of mental models between different domains. Not different kingdoms.

If music and art were considered “fringe” and we wanted to talk about mental models at the domain level we could say:

Literature is textual causing people to lean towards a single approach to forming mental models within the arts.

A majority of programmers will make the point that textual languages are the only way to program a computer: noting that textual languages are remarkable in their compactness.

Textual languages are used to program computers and used by programmers to form mental models. This is why you shouldn’t interrupt a programmer. However, people form mental models using more than just textual languages.

The point we are raising is this:

Programming languages are textual causing people to lean towards a single approach to forming mental models of programs.

Why have we put some much time and effort into using a single approach to program computers, textual languages, when people form mental models in so many different ways?

I was lucky to have a chat with Paul Morrison, the inventor of flow-based programming, and he had this to say on the directions computers could have taken (a perspective from 1968):

Computers evolved out of machines with one instruction counter. Computers could have been anything so if we had trouble giving them instructions it was our fault. We essentially became brainwashed into believing that computers, and computer languages, had to be that way, and generations of programmers were trained to think this way. But there was a time early on when we could have gone a different way.

So, let’s step back some and see if there are other practical approaches to programming computers.

I can’t read sheet music.

I can imagine that people who read sheet music can not only play a song on instruments but also hear that song in their head by simply looking at the sheet music.

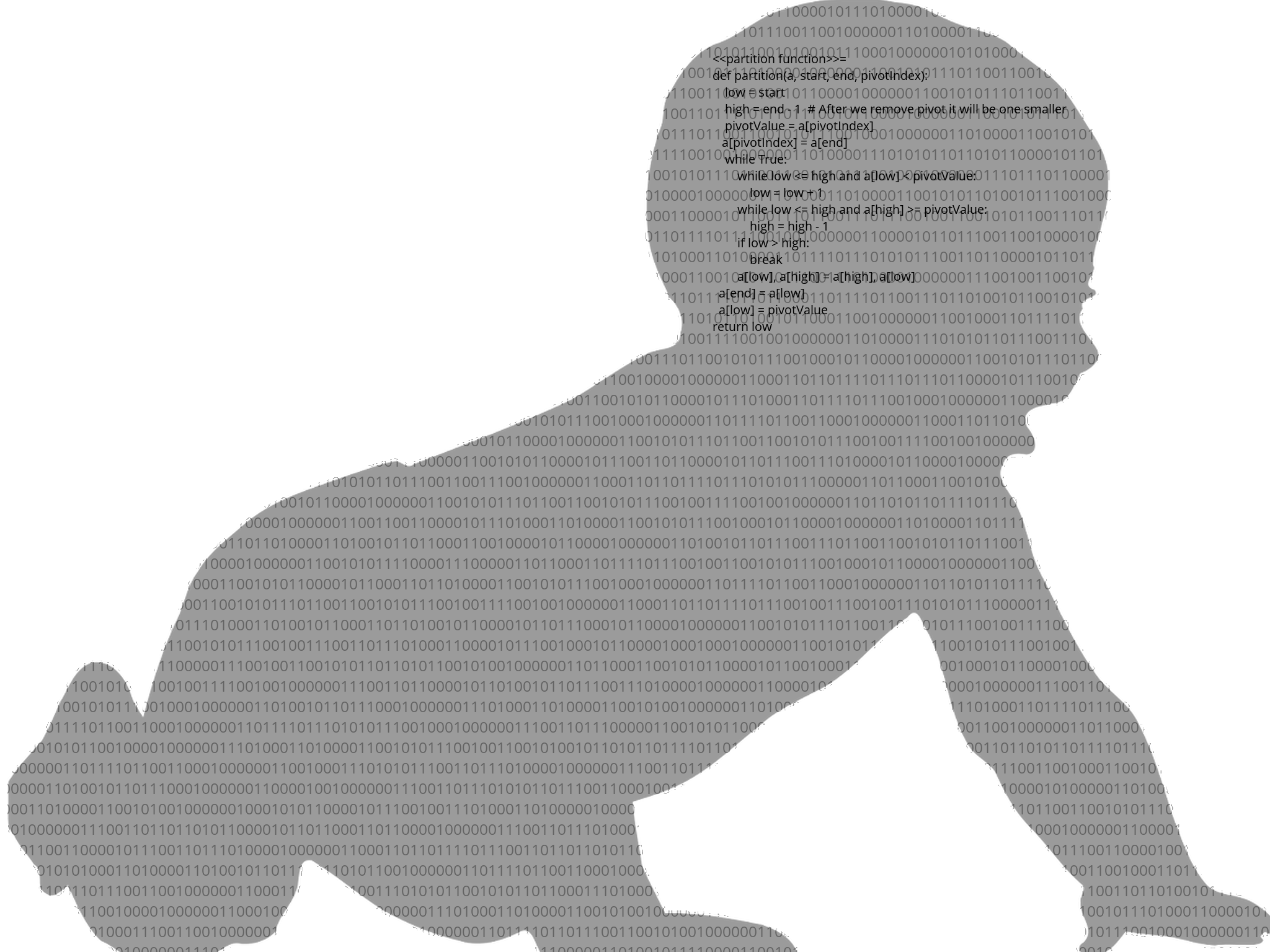

###### Image-1.2: Tibetan musical score (image source) {#id-i1-2}

It is only after years of practice that people are able to build a mental model of music by reading sheet music. Sheet music has been around for hundreds of years remaining basically unchanged. Considering current day technology, is it really the best way to represent music today?

My guess is that one of the reasons why sheet music is still so prevalent is because millions of people have put a lot of effort into being able to read it.

An experienced mathematician doesn’t just see an equation when looking at the Pythagorean theorem. They see much more.

###### Image-1.3: The Pythagorean theorem (created using Codecogs) {#id-i1-3}

A mathematician is able to manipulate the pythagorean theorem in their head building out new ideas and new understandings. They are able to form mental models of what these equations mean. Again, this takes years of study and practice to master. Similar to sheet music, a lot of resources have been invested in training people to use math to build mental models.

So, if I am an experienced mathematician programming mathematical equations into a computer, which representation would I prefer?

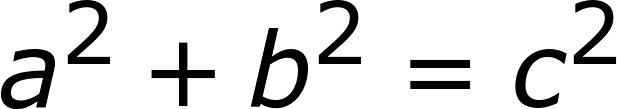

###### Image-1.4: What if Mathematicians could program a computer using actual mathematical symbols? {#id-i1-4}

For math and music, people are using different ways to communicate information between their peers. Not only is the representation different, but the understanding built around the mental models is also different.

To argue that one of these approaches could be used universally would be difficult. How would maths compactness hold up as sheet music?

Perhaps, then, we should reconsider the argument that textual languages are the way to program because they are so compact. Perhaps there are situations where other representations are much more effective at helping programmers build mental models.

Perhaps, like sheet music, textual languages are so prevalent because millions of people hours have been spent learning and using textual languages to program computing devices?

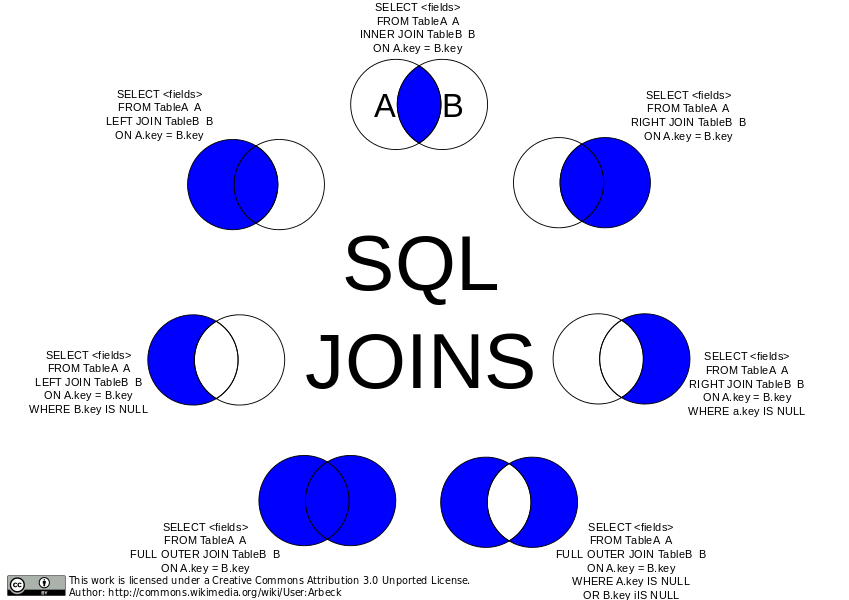

SQL is a textual language, an algebra, used to describe relationships between relations. A SQL statement to query the database looks something like this:

SELECT A.*, B.*

FROM A

INNER JOIN B ON B.key = A.key

Yet, that same statement above can be represented visually using sets.

###### Image-1.5: What if sets could be used to program a computer (Image Source)? {#id-i1-5}

It takes a while to master SQL. Often, when people learn SQL, they are shown something like Image-1.5 to help them form a mental model of what the SQL statement is actually doing (Visual Representations of SQL Joins).

Why use sets to teach people how to program only to end up using a textual language, SQL, to actually program the computer? Is the compactness of SQL really so great as to ignore all the prior knowledge and skill people have acquired learning set theory?

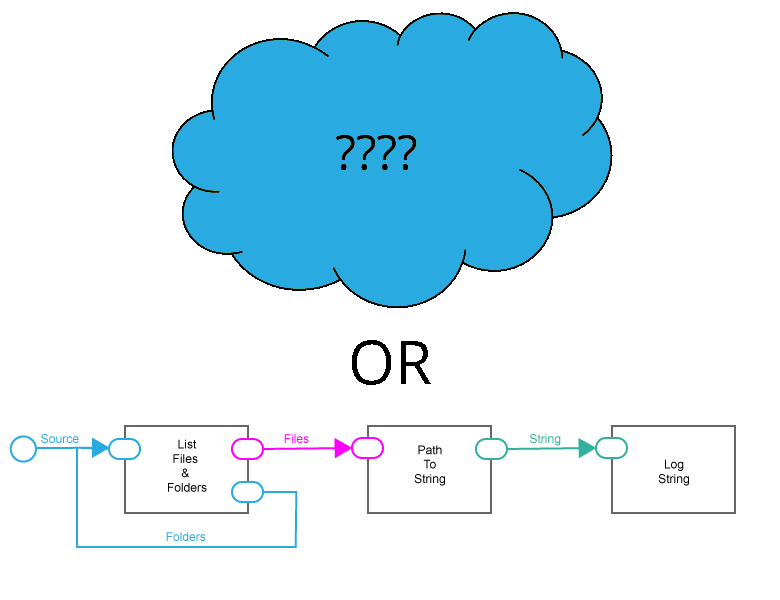

Flow-based programming is an approach to programming that uses asynchronous systems as opposed to the more synchronous nature of traditional computing devices.

I wanted to create an image similar to the “which visual representation would mathematicians prefer” but wouldn’t even know where to start in trying to represent asynchronism using a textual language (there are just so many approaches).

Image-1.6 is showing more than just a program to list some files. It is showing us a fully scalable, big data-esque, highly asynchronous, highly scalable program to list files.

###### Image-1.6: Flow-based programming is great at representing asynchronous systems (image source). {#id-i1-6}

In fact, describing asynchronous execution using textual languages is really difficult. Using flow-based programming, and the associated visual representation, we are able to quickly build out a mental model of what is happening within the computer.

We do need to be careful to not make the mistake of pushing FBP as the “one way” to represent a program. It is a great way to represent asynchronous manipulation of big-data. However, it might not be the best way to represent a mathematical equation: even if that equation could be executed asynchronously.

It is becoming apparent that there is really no one best way to help people form mental models of what a computer program is doing. In some cases sets may be better, sometimes flow-based programming would do the job, in other cases a mathematical equation and sometimes we need to fall back to textual languages.

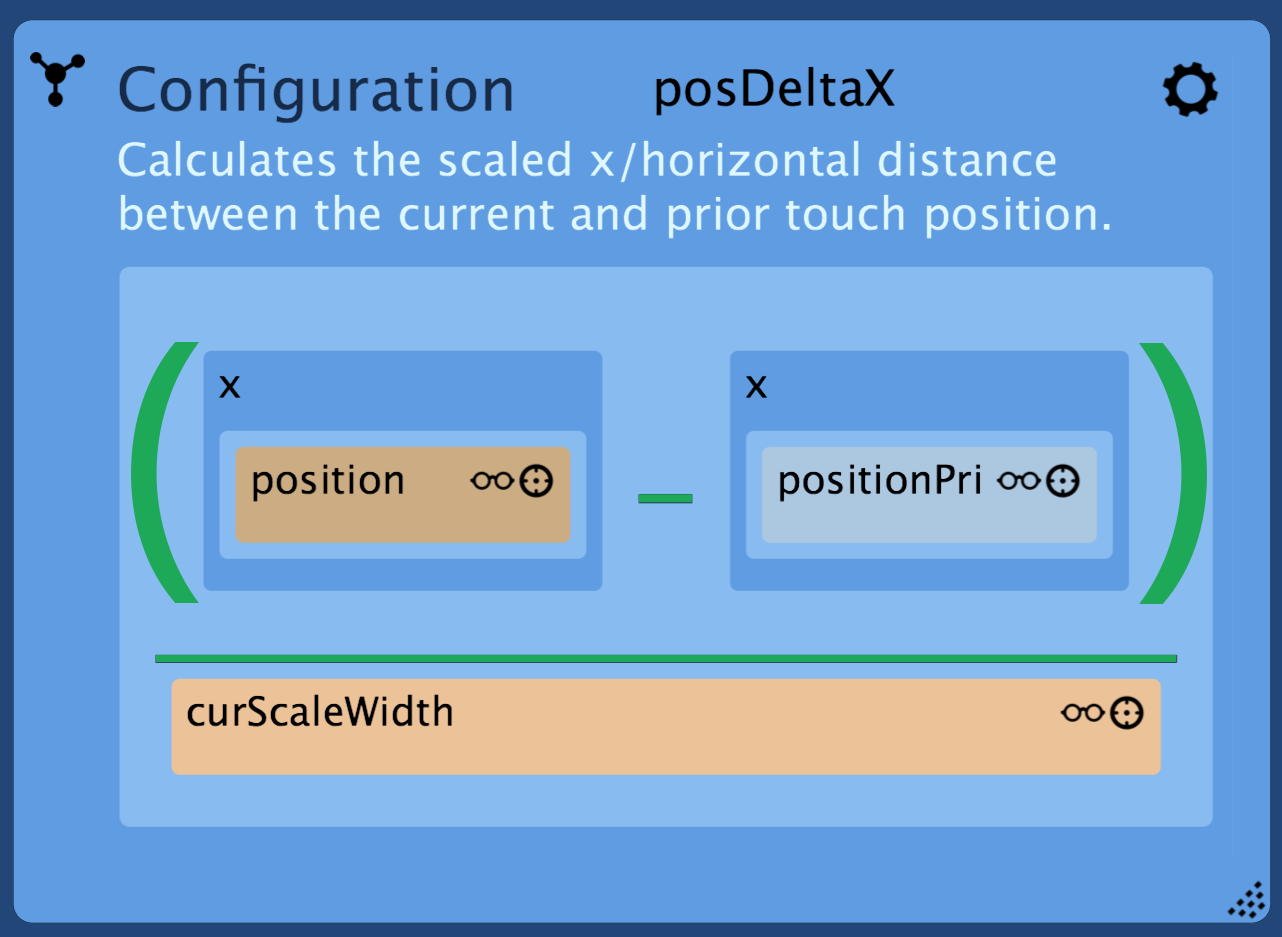

Instead of the “one VPL to rule them all” approach to the representation of a program, Interface Vision is building out a domain-agnostic VPL that is able to represent programs in a multitude of visual representations. A VPL for VPLs.

###### Image-1.7: Interface Vision’s VPL is able to show multiple representations of the same program logic. {#id-i1-7}

The light blueish area of Image-1.7 contains a mathematical equation (Yes. We are looking for help from UX/UI designers).

The same blueish area could contain other types of VPLs including a finite state machine, a flow-based program and even source code.

We are able to build upon our users particular domain experiences as opposed to requiring them to learn one or more textual languages.

One of the pain points of learning how to program is learning how to form mental models of problems using textual languages. There is no single mental model for programming (something VPLs have also been guilty of by trying to create single representational models).

Providing an environment that allows people to program a computer within their field of expertise opens up computers to more people and is one more step towards the democratization of programming.

The next pain point to melt away is the technological aspects of creating a VPL for VPLs. The solution is almost as old as computers themselves: messages.

If you find our work interesting and look forward to reading our next post on messaging, please follow us @interfaceVision and/or @erichosick.