by Eric Hosick (erichosick@interfacevision.com)

Eventually, programming will be done by composing software visually: not through coding.

This is inevitable.

Interface Vision is a visual object language and fully composable object framework. Instead of developing software using source code, programmers develop by visually connecting parts (1) together.

Interface Vision is written in C# using Xamarin, Mono, Monodevelop, Mono Touch and Visual Studio.

We’re creating Interface Vision using a programming paradigm, we developed in-house, called Simple Interface Programming (SIP).

Before we delve into Interface Vision, let’s talk about SIP and how it has allowed us to create Interface Vision.

SIP does not use functions or methods. Yes. Really. Our framework has tens of thousands of lines of source code and we have one function:

static int main {

...

}

Wait. If we have no functions or methods, then how do we:

SIP use properties, instead of methods, to define the tasks a part performs. Notice, in Source-1.1, withLong contains the task to add two numbers.

...

public long withLong {

get { return opLeft.withLong + opRight.withLong; }

}

...

SIP doesn’t allow developers to create subroutines (methods, functions, modules, etc.) which take parameters.

In SIP, we don’t really pass information to a part. Instead, we “pull” that information into the part. How do we do this?

Traditionally, properties and attributes store information internal to a part. External information is provided to parts through parameters.

This is where SIP differs. Within SIP, a property can contain a reference to external information.

This “reference” is actually a special type of part, called a locator, which is able to locate information contained within data structures. For example, a HashTable would have a HashTableLocator and an Array would have an ArrayLocator.

Since Interface Vision is a visual programming language, users drag and drop parts to create instanced of them. Usually, a user will attach a new part to the property of an existing part.

We store and load all of these attached parts in a configuration file using serialization. An example of just such a configuration is shown in Source-1.5 and Source-1.7.

It is also possible to initialize parts using source code as shown in Source-1.3.

Let’s say we want to add two numbers (longs, integers, etc.). Addition takes a left operand and a right operand. Traditionally, add is defined as a function (or a method) as follows:

long add ( long opLeft, long opRight ) {

return opLeft + opRight;

}

int add ( int opLeft, int opRight ) {

return opLeft + opRight;

}

However, in SIP, you aren’t allowed to use parameters. Instead we use properties.

We create an Add part with properties as shown (2):

public interface IPart {

long withLong { get; set; }

int withInt { get; set; }

}

public class Add : IPart {

public IPart opLeft { get; set; }

public IPart opRight { get; set; }

public long withLong {

get { return opLeft.withLong + opRight.withLong; }

}

public long withInt {

get { return opLeft.withInt + opRight.withInt; }

}

} ###### Source-1.1: The Add Part can add two numbers. {#id-s1-1}

The first thing to note is that the properties opLeft (the left operand of add) and opRight (the right operand of add) are not primitive data types. They are of type IPart.

...

public IPart opLeft { get; set; }

public IPart opRight { get; set; }

...

If we want to add two long or integer primitive data types, we will need to call the withLong or withInt property of IPart. This is seen within the implementation of Add.

...

public long withLong {

get { return opLeft.withLong + opRight.withLong; }

}

public long withInt {

get { return opLeft.withInt + opRight.withInt; }

}

...

This means we will need a Long part and an Int part to hold the value of a primitive data type.

public class Long : IPart {

public long value { get; set; }

public long withLong {

get { return value; }

}

public int withInt {

get { return (int)value; }

}

}

public class Int : IPart {

public int value { get; set; }

public long withLong {

get { return value; }

}

public int withInt {

get { return value; }

}

} ###### Source-1.2: A Long and Int part. {#id-s1-2}

So, let’s see how we compose addition using C# object initializers:

static void main() {

IPart program = new Add {

opLeft = new Long { value = 5 },

opRight = new Long { value = 7 }

};

long result = program.withLong;

} ###### Source-1.3: Our first program simply adds two numbers. {#id-s1-3}

The result of adding two numbers is found by simply calling myProgram.withLong.

long result = program.withLong;

We could use the same composed part to get the result as an integer.

int result = program.withInt;

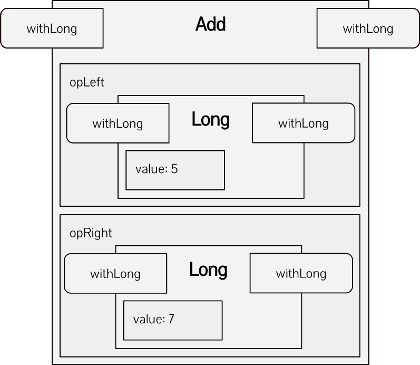

We can visually represent our add configuration using a diagram (NOTE: We’ve come to the conclusion that the best way to represent Add visually is to stick with mathematical equations. The post “there is no single mental model for programming” goes into detail on why we’ve made this decision).

###### Figure-1.1: An example of adding two numbers internal to a part.

In this example, the information located in the properties is internal to the add part. Let’s look at an example where the information is external.

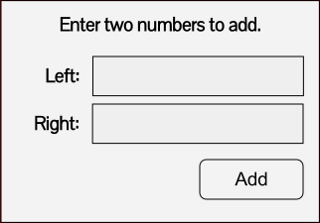

Figure-1.2 is a form that has two fields. When we press “Add” on the form, two numbers are summed (3).

###### Figure-1.2: A form which adds two numbers.

We are only allowed to compose programs and we can’t provide information via a public method with parameters. So, we need to create a part that can locate information on a form. Let’s call it FormValue (4).

public class FormValue : IPart {

public string nameForm { get; set; }

public string nameField { get; set; }

public long withLong {

get { return Ccm.shared[nameForm].field[nameField].withLong; }

}

public long withInt {

get { return Ccm.shared[nameForm].field[nameField].withInt; }

}

} ###### Source-1.4: The FormValue Part is able to retrieve a value from the field of a form. {#id-s1-4}

The example code in Source-1.4 is almost boilerplate except the global Part called Ccm (which stands for Composite Centric Memory (CCM) ).

...

get { return Ccm.shared[nameForm].field[nameField].withLong; }

...

Here is an example usage (6):

static void main() {

IPart program = new Add {

opLeft = new FormValue {

nameForm = “AddForm”,

nameField = “opLeft”

},

opRight = new FormValue {

nameForm = “AddForm”,

nameField = “opRight”

}

};

long result = myProgram.withLong;

} ###### Source-1.5: The values to add are external to the Add part. {#id-s1-4}

A visual representation of this example is shown in Figure-1.3.

###### Figure-1.3: An example of adding two numbers external to a part.

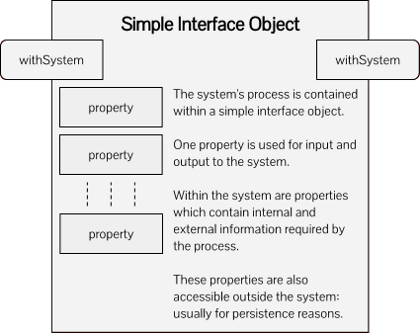

What is interesting about the parts we have created is that they all have similar interfaces: they all look the same to an external observer. However, internally, these parts are doing completely different things.

In the first example, when Add calls withLong of the instance plugged into the opLeft (or opRight) property, a value is simply returned from the Long. However, in the second example, Add ends up using a part that reads from a form. Two completely different tasks which, from an external observer, look like they are doing the exact same thing.

Since the interface is the exact same between Long, Int and FormValue, Add is fully unaware of where the values are coming from. This means that the part which Adds is not “connected” to the part that finds the value on the form: they are decoupled (7).

Figure-1.4 shows how we can standardize the interface of our parts. Every part has the exact same interface 8. This makes them a lot easier to use than traditional objects and modules which have specialized, and thus unique, interfaces.

###### Figure-1.4: All parts have a standardized interface.

Using traditional programming paradigms, you end up with thousands of objects: each with their own unique method signature/interface. With SIP, you end up with thousands of Parts with the same signature/interface.

If programs are created visually, then how are they saved? Are they compiled or interpreted like traditional programs?

Programs created using Interface Vision are neither compiled or interpreted. Programs are stored as data in different formats 8. The program is loaded from one of the stored data formats and deserialized into parts that form the executable program. The parts have already been written and compiled by us, so there is no need for you to compile the programs you create. In fact, the program is always running: even while you are developing it.

Here is an example of a program described and stored as json (a standard format used to store the state of a Part).

{

"$type": "Add",

"opLeft": {

"$type": "FormValue",

"nameForm": "AddForm",

"nameValue": "opLeft",

},

"opRight": {

"$type": "FormValue",

"nameForm": "AddForm",

"nameValue": "opRight",

},

} ###### Source-1.6: A Configuration using json. {#id-s1-6}

What is really interesting about this json is that it looks very similar to the example C# in Source-1.6. In fact, there is an almost one-to-one relationship between the persisted version a program and the program written using C# object initializers.

Our parts have no methods: only properties. This greatly simplifies database usage (both Sql and non-sql solutions). The only difference between traditional objects and relations in a relational databases was that objects have methods and properties whereas relations only have properties. Since our Parts have no methods, they can also be viewed as relations.

This means any Part can be directly stored in a database without any need to convert the Part.

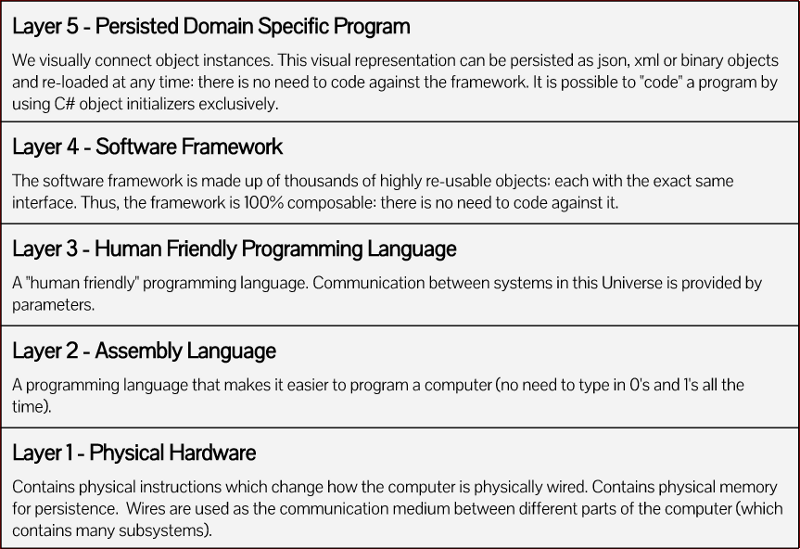

Using SIP, software layers differ slight from traditional programming paradigms as seen in Figure-1.5.

###### Figure-1.5: Software layers using SIP.

Layer 4 is the software framework. It contains all the Parts that are available to the developer when programming. A drawback is that if a new type of Part is required, the developer would need to update or add it to the framework.

Layer 5 is a domain specific program created by visual composition . The result of the program is a data file in the form of json, xml or other format. This file can be stored anywhere: even in the cloud or in a database. It can be loaded in different environments such as iOS, Android, OSX and Windows.

The domain specific business logic is 100% removed from the programming language and framework. This makes it easier to create cross platform applications (among other advantages).

Interface Vision has some of the following advantages over traditional methods of development:

The final “secret” of Interface Vision and SIP is composite centric memory. Composite centric memory has the following key aspects:

A developer is required to place parts they compose in composite centric memory. The format of the CCM is not important: it can be any type of data structure or even a collection of different types of data structures. However, for every program there is a single “root” by which all information is accessible. Special locator Parts have been written to find information within CCM.

Information in CCMs can be stored as follows:

CCM allows access to all external information required by any part to accomplish that part’s task.

Note, this is not similar to a global variable in that a part accesses a CCM via locators. Programmers should not access CCM directly (and really they can’t since they are not allowed to code: they can only compose using existing types).

One issue that comes up is multi-threaded programs. It is often necessary for a function or method to be used by different threads at the same time. This means any data shared between these programs, even within the method or function, needs to be “protected” in some way. We don’t want two programs updating the same data at the same time.

We solve this problem in a few ways:

Duplicate a CCM - Optimally, we want to remove the need for a developer to make their code thread safe. The most desirable solution, then, is taking advantage of the properties of CCMs. A program is composed of Parts. To create a new instance of an entire program, you just duplicate the CCM for that program and run it in a thread. You are assured that everything within that CCM instance is only accessed by the current thread. You don’t have to even consider thread safe code.

Mutex A Part - A property that needs to be thread safe can be wrapped or decorated with a Mutex type. An example of just such a mutex type is provided below.

public class Mutex : IPart {

public string nameOfMutex { get; set; }

public IPart wrappedItem { get; set; }

public long withLong {

get {

long temp = 0;

Ccm.shared.mutext[nameOfMutex].enter = this;

temp = wrappedItem.withLong;

Ccm.shared.mutext[nameOfMutex].exit = this;

return temp;

}

set {

Ccm.shared.mutext[nameOfMutex].enter = this;

wrappedItem.withLong = value;

Ccm.shared.mutext[nameOfMutex].exit = this;

}

}

public long withInt {

get {

int temp = 0;

Ccm.shared.mutext[nameOfMutex].enter = this;

temp = wrappedItem.withInt;

Ccm.shared.mutext[nameOfMutex].exit = this;

return temp;

}

set {

Ccm.shared.mutext[nameOfMutex].enter = this;

wrappedItem.withInt = value;

Ccm.shared.mutext[nameOfMutex].exit = this;

}

}

} ###### Source-1.7: A Mutex Part. {#id-s1-7}

Here is an example usage that makes our above Add json example thread safe:

{

"$type": "Mutex",

"nameOfMutex": "AddMutex",

"wrappedItem": {

"$type": "Add",

"opLeft": {

"$type": "FormValue",

"nameForm": "AddForm",

"nameValue": "opLeft",

},

"opRight": {

"$type": "FormValue",

"nameForm": "AddForm",

"nameValue": "opRight",

}

}

} ###### Source-1.8: Add configured with a mutex. {#id-s1-8}

Consider for a moment that the example Mutex type is fully re-usable. It can be plugged into any property! The same approach can be used for things like exception handling.

Allocating memory can be expensive. Interface Vision is able to minimize memory allocation during run-time. A program is composed solely of Parts. These parts are first loaded when the configuration is deserialized from json, xml, etc. They stay around for the lifetime of the program. This means an entire program can be configured that requires no memory allocation during run time.

Let’s consider a configuration for logging a user into a web based system. Let’s say we want to have up to 400 people a second logging in and it takes 1 second to log them in. Our configuration is able to login a single user. That configuration is then stored in a Factory part that is able to pre-allocate as many of our log-in programs as we require: 400 in this case.

For every login, we ask for a login configuration from the Factory, run that login based on some varying information (perhaps username and password), and return that configuration to the factory when we are done. If all 400 programs are in use, the Factory can create a new instance of the entire program which would require memory allocation.

This leads to faster execution of programs as there is no need to allocate or deallocate memory during run-time.

This also makes for programs that are cloud friendly as they can be easily scaled. We don’t have to worry about our code being thread safe meaning it will run faster 13.

{#id-1} 1. We look at parts as being “similar” to systems, objects, classes, modules, functions, subroutines and the such.

{#id-2} 2. Our example source code is written in C#.

{#id-3} 3. Note that we do not provide a configuration for the form itself. This was done to keep the example simple.

{#id-4} 4. We could generalize the idea of locating information within our framework.

{#id-6} 6. Note that, to keep the example simple, we do not provide a configuration for the form itself. The Form class would be part of the vision framework. Instantiating and defining the form would be done in the exact same manner as was done with the Add program.

{#id-8} 8. The properties themselves are accessible externally but really only used directly during serialization and deserialization.

{#id-9} 9. Programs can be stored as json, xml, binary data, and even as key/value pairs in a database.

{#id-10} 10. Remember, the program could also be created by using C# object initializers and then compiled or someone could “program” in json (although this is frowned upon).

{#id-11} 11. The framework is specifically designed to be composed visually: not coded against. However, coding is possible using C# object initializers.

{#id-12} 12. Traditionally, data structure objects support both the structure and the searching of that structure. This does seem to violate the single-responsibility principle.

{#id-13} 13. Code that is thread safe usually requires some kind of operating system call slowing down the code in general: even when it is not being used in a multi-threaded environment.